Michael Faraday

| Michael Faraday | |

|---|---|

| |

| Species | Human |

| First appearance | Mario's Time Machine (1993) |

- “Big machines? What an imagination! As big as your magnetic personality, Mario! I’m not sure what its use will be yet, but I’ll wager the government will some day tax it!”

- —Michael Faraday, Mario's Time Machine

Michael Faraday (22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) in the Super Mario franchise is an English scientist who studied into the fields of physics and chemistry, notably identifying benzene. He was also this in real life, and was born to a poor blacksmith and became the apprentice of a bookbinder at a young age. He became interested in science and attended the lectures of Humphry Davy at a young age. He was self-educated and submitted a bunch of the notes he took to Davy, and he soon became Davy's apprentice. Under him, Faraday became an excellent scientist, becoming a lecturer in his own right that made scientific lectures interesting for the average person and especially children, and most notably discovering the link between magnetic fields and electricity (later called Faraday's law of induction).

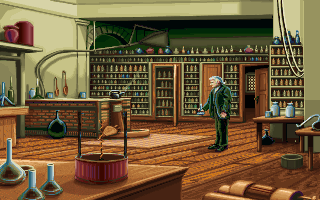

Michael Faraday appears only in Mario's Time Machine. Here, Bowser traveled to 1831 to steal the Magnet that Faraday used for his experiments, preventing him from completing his discoveries. When Mario time-travels back to the same year, he finds Michael Faraday in his laboratory. Since Mario does not know that the Magnet belongs to Faraday, if he talks to Faraday regardless, he asks if he has discovered Faraday, and Faraday replies that he has. Faraday says that he is on the verge of an "electrifying" discovery, and he does not want Mario to disturb him. Mario then asks various nearby people, including Faraday's wife, Sarah Barnard, about Faraday and the Magnet. After absolute certainty that the Magnet belongs to Faraday, Mario returns to the laboratory and tells Faraday that he has found his Magnet. Faraday excitedly takes the Magnet and immediately puts it to use in his experiment. Faraday explains that his experiment involves generating a current of electricity when he passes the Magnet through a coil of wire. Mario remarks that Faraday is now able to power big machines, and Faraday is surprised by Mario's audacious comments. Faraday is unsure what practical applications his findings may have, but he is sure that the government plans to tax it.

There are many historical discrepancies between the Michael Faraday of the Super Mario franchise and in real life:

- A young boy who says that Michael Faraday's first lecture within the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures was The Chemical History of a Candle. However, not only did he give several lectures before this one, he gave it in 1848.[1] He also talks about how Charles Dickens wrote about Faraday's lectures, which he only did after Faraday had presented The Chemical History of a Candle.[2]

- Charles-Gaspard de la Rive discusses a lecture in which Faraday demonstrates an electromagnet by throwing a shovel, a pair of tongs, and a poker at it. Not only did this lecture take place in 1856, but he threw a coal scuttle and not a shovel.[3]

- Sarah Barnard characterizes Faraday's former mentor, Humphry Davy, as someone who was utterly jealous of Faraday's success and generally rude towards him, but that view is careless, ignoring much of the relationship between Davy and Faraday.[4][5] She also remarks that Faraday noted that the date with the most happiness to him was the day that the two of them married. While this is true, he only noted so in 1847.[6]

- Several characters are waiting for Faraday's upcoming lecture, but he did not give a Christmas Lecture in 1831.[1]

- The history pages state that Faraday is the only scientist to have both an SI unit and a physical constant named after them, despite the real-life Isaac Newton and Charles-Augustin de Coulomb sharing the honor.[7][8]

References[edit]

- ^ a b (2014). "History of the CHRISTMAS LECTURES". Royal Institution. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ Melville, Wayne (June 17, 2010). "Michael Faraday's Popular Science Lectures, Percival Leigh, and Charles Dickens: Science for the Masses in 'Household Words' (1850-51)". The Victorian Web. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Silvanus P. (1901). "Royal Institution Lectures" - Michael Faraday: His Life and Work. Cassell and Company. Page 237.

- ^ Fraser, James (Feb. 1836). "Gallery of Literary Characters. No. LXIX. Michael Faraday, F.R.S., HON. D.C.L. OXON, Etc. Etc.". Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country. Page 224.

- ^ Knight, David M. (1985). "Davy and Faraday: Fathers and Sons" - Faraday Rediscovered. ISBN 978-1-349-11139-8-3. Page 33–49.

- ^ Gladstone, John Hall (2010). "Study of His Character" - Michael Faraday. ISBN 978-1988357867. Page 70–71.

- ^ Wikipedia contributors (August 22, 2017). "List of scientists whose names are used as SI units". Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ Wikipedia contributors (June 23, 2017). "List of scientists whose names are used in physical constants". Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

| People | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Game designers | Goro Abe • Stephen Dupree • Koichi Hayashida • Shigefumi Hino • Takehiko Hosokawa • Sébastien Isaia • Toshiharu Izuno • Ryota Kawade • Hiroyuki Kimura • Hiroji Kiyotake • Yoshiaki Koizumi • Hideki Konno • Don Lloyd • Hirofumi Matsuoka • Gregg Mayles • Kenji Miki • Shigeru Miyamoto • Naoko Mori • Stephen Mortimer • Kenta Motokura • Shiro Mouri • Ryuichi Nakada • Satoru Okada • Yoshio Sakamoto • Masahiro Sakurai • Hiroshi Sato • Taku Sugioka • Risa Tabata • Shugo Takahashi • Ko Takeuchi • Kensuke Tanabe • Takashi Tezuka • Kenta Usui • Kosuke Yabuki • Hitoshi Yamagami • Yasuhisa Yamamura • Katsuya Yamano • †Gunpei Yokoi | ||||

| Voice actors and actresses | Video games | Current | Kevin Afghani • Dawn M. Bennett • Nate Bihldorff • Christine Marie Cabanos • David Cooke • Caitlyn Elizabeth • Dan Falcone • Giselle Fernandez • Ashley Flannegan • David J. Goldfarb • Kate Higgins • Ryan Higgins • Michelle Hippe • Hitomi Hirose • Nobuyuki Hiyama • Kenneth W. James • Samantha Kelly • Yuki Kodaira • Shohei Komatsu • Carlee McManus • Tsuguo Mogami • Tadd Morgan • Takashi Nagasako • Zoe Nelson • Caety Sagoian • Kahoru Sasajima • Go Shinomiya • Laura Faye Smith • Katsumi Suzuki • Motoki Takagi • Kazumi Totaka • Toshihide Tsuchiya • Mick Wingert | ||

| Former | Julien Bardakoff • Jocelyn Benford • Justin Berti • Scott Burns • Jessica Chisum • Stevie Coyle • †Kate Fleming • Marc Graue • Kit Harris • Kelsey Hutchison • Eriko Ibe • Kerri Kane • Grant Kirkhope • Asako Kozuki • Dex Manley • Isaac Marshall • Charles Martinet • Tomoko Maruno • Nicole Mills • Lani Minella • Deanna Mustard • Eric Newsome • Eveline Novakovic • Christina Peyser • Dolores Rogers • Mercedes Rose • Thomas Spindler • Chris Sutherland • Leslie Swan • Jen Taylor • Satsuki Tsuzumi • Mike Vaughn • Stephan Weyte | ||||

| WarioWare series | Edward Bosco • Alejandra Cazares • Robbie Daymond • Todd Haberkorn • Kyle Hebert • Melissa Hutchison • Erica Lindbeck • Griffin Puatu • Tyler Shamy • Stephanie Sheh • Keith Silverstein • Owen Thomas • Rebeka Thomas • Vegas Trip • Cristina Vee • Fryda Wolff | ||||

| Mario + Rabbids series | Kaycie Chase • David Coburn • Lee Delong • Yuriko Fuchizaki • David Gasman • Matthew Géczy • Hiroki Goto • Atsushi Imaruoka • Nobuaki Kanemitsu • Mitsuaki Kanuka • Lexie Kendrick • Margaeux Lampley • Yasuhiro Mamiya • Sharon Mann • Eriko Matsui • Shin Matsushige • Farahnaz Nikray • Bruce Sherfield • Hana Takeda • Barbara Weber-Scaff • Laurie Winkel • Toa Yukinari • Chisa Yuuki | ||||

| Cartoons | †Lou Albano • †Harvey Atkin • †Walker Boone • Bart Braverman • Donald Burda • Ben Campbell • Peter Cullen • Damon D'Oliveira • Jeannie Elias • Toru Furuya • Dan Hennessey • †Gordon Masten • Tracey Moore • Greg Morton • James Rankin • †Tony Rosato • Andrew Sabiston • Tabitha St. Germain • Michael Stark • John Stocker • Stuart Stone • Judy Strangis • Tara Strong • †Milton "Soupy Sales" Supman • †Aron Tager • Joy Tanner • Louise Vallance • †Milli Vanilli • Frank Welker • †Danny Wells • Richard Yearwood | ||||

| Films | English | Fred Armisen • Eric Bauza • Jack Black • Charlie Day • Jessica DiCicco • John DiMaggio • Juliet Jelenic • Keegan-Michael Key • Sebastian Maniscalco • Charles Martinet • Scott Menville • Khary Payton • Chris Pratt • Kevin Michael Richardson • Seth Rogen • Rino Romano • Anya Taylor-Joy | |||

| Catalan | Roser Aldabó • David Brau • Juan Antonio Bernal • Ramón Canals • Eduard Doncos • David Jenner • Ivan Labanda • Jaume Mallofré • Charles Martinet • Carla Mercader • Albert Mieza • Pep Papell • Oriol Rafel • Albert Trifol Segarra • Tony Sevilla | ||||

| Japanese | Tasuku Hatanaka • Naomi Kusumi • Yasuhiro Mamiya • Kenta Miyake • Mamoru Miyano • Tomokazu Seki • Arisa Shida • Kōji Takeda • Jin Urayama • Ann Yamane • †Kōsei Tomita • †Takanobu Hozumi • Noriko Hidaka • †Ryōko Kinomiya • Kazuhiko Inoue • Shigeru Chiba | ||||

| European French | Paul Borne • Mathieu Buscatto • Jérémie Covillault • Kaycie Chase • Thierry Desroses • Benoît DuPac • Xavier Fagnon • Emmanuel Garijo • Christophe Lemoine • Nicolas Marié • Charles Martinet • Céline Monsarrat • Marc Perez • Dorothée Pousséo • Boris Rehlinger • Donald Reignoux • Audrey Sourdive • Pierre Tessier | ||||

| German | Patrick Baehr • Sven Brieger • Marios Gavrilis • Luiza Kampf • Matthias Klages • Matti Klemm • Leonhard Mahlich • Axel Malzacher • Charles Martinet • Tobias Meister • Timmo Niesner • Dirk Petrick • Sven Plate • Dalia Schmidt-Foß • Gerrit Schmidt-Foß • Bernhard Völger • Daniel Welbat | ||||

| Italian | Alessandro Ballico • Nanni Baldini • Alessandro Budroni • Paolo Buglioni • Emiliano Coltorti • Valentina Favazza • Francesco De Francesco • Franco Manella • Charles Martinet • Giulietta Rebeggiani • Gabriele Sabatini • Claudio Santamaria • Edoardo Stoppacciaro • Fabrizio Vidale • Paolo Vivio | ||||

| Brazilian Portuguese | Filipe Albuquerque • Pedro Azevedo • Paulo Bernardo • Marcos Castro • Enzo Dannemann • Márcio Dondi • Eduardo Drummond • Carina Eiras • Marcus Eni • Cid Fernandes • Monique Filardy • Marcelo Grativol • Ricardo Juarez • Léo Rabelo • Lacarv • Bernardo leGrand • Regina Maria Maia • Jeane Marie • Charles Martinet • Andrea Murucci • Giuseppe Oristanio • Karen Padrão • Manolo Rey • Marco Ribeiro • Raphael Rossatto • Leonardo Serrano • Daniel Simões • Jéssica Vieira | ||||

| European Portuguese | Pedro Bargado • Luís Barros • Claudia Cadima • Alexandre Carvalho • Laura Dutra • Bruno Ferreira • Eduardo Frazão • Fernando Luís • António Machado • Catarina Machado • Charles Martinet • Tobias Monteiro • José Nobre • Rui Oliveira | ||||

| Romanian | Virgil Aioanei • Cătălina Chirțan • Marcelo Cobzariu • Adi Dima • Andrei Duțu • Alexandru Georgescu • Ionuț Grama • Adina Lucaciu • Charles Martinet • Conrad Mericoffer • Andrei Radu • Marius Săvescu | ||||

| European Spanish | Pablo Adán • Juan Alfonso Arenas • Fernando "Nano" Castro • Fernando Cordero • Felipe Garrido • Valeria Garzón • Miguel Ángel Garzón • Fernando de Luis • Charles Martinet • Txema Moscoso • Iván Muelas • Laura Pastor • David Robles • Guillermo Romero • Rafa Romero • María Jesús Varona | ||||

| Latin American Spanish | Santos Alberto • Raúl Anaya • Diego Becerril • Alberto Bernal • Gaby Cárdenas • Roberto Carrillo • Victoria Céspedes • Elsa Covián • Ernesto Cronik • Víctor Delgado • Héctor Estrada • Germán Fabregat • María Fernanda Morales • Luis Leonardo Suárez • Agustín López Lezama • Óscar López • Rodrigo Luna • José Antonio Macías • Charles Martinet • Monserrat Mendoza • Mauricio Pérez • Harumi Nishizawa • Gabriela Ortiz • Ale Pilar • Mark Pokora • Jocelyn Robles • Jorge Roig • Jorge Roig Jr. • Tommy Rojas • Miguel Ángel Ruiz • Víctor Ruiz • Roberto Salguero • Erick Selim • Rubén Trujillo • Alex Villamar | ||||

| Actors and actresses | †Lou Albano • Jason Bateman • †Joe Bellan • †Harry Blackstone Jr. • Brian Bonsall • †Christopher Collins • Nicole Eggert • †Dennis Hopper • †David Horowitz • †Bob Hoskins • Ernie Hudson • Magic Johnson • †Jim Lange • Cyndi Lauper • John Leguizamo • †Pam Matteson • Alyssa Milano • †Mojo Nixon • Patrick Pinney • †Rowdy Roddy Piper • Sgt. Slaughter • †Shabba-Doo • Rob Stone • Andrew Trego • †Danny Wells | ||||

| Composers and sound engineers | Toshiki Aida • Shinobu Amayake • Hirokazu Ando • Daichi Aoki • Atsuko Asahi • Toru Asakawa • Ryosuke Asami • Misaki Asada • Yasuhisa Baba • Taro Bando • Robin Beanland • Gareth Coker • Sayako Doi • Shiho Fujii • Akira Fujiwara • Shigetoshi Gohara • Martin Goodall • Minako Hamano • Asuka Hayazaki • Christophe Héral • Jamie Hughes • Norio Hanzawa • Yoshito Hirano • Kanji Hirao • Kenji Hikita • Yoshikata Hirota • Takeshi Hama • Tadashi Ikegami • Masayoshi Ishi • Yasuaki Iwata • Fumihiro Isobe • Daichi Ishihara • Kozue Ishikawa • Yasushi Ida • Yoshimasa Ikeda • Shauny Sion Jang • Chris Jojo • Takeru Kanazaki • Hideki Kanazashi • Yukio Kaneoka • Grant Kirkhope • Takashi Koiwa • Koji Kondo • Naoto Kubo • Takashi Kouga • Rei Kondoh • Naruki Kadosaka • Yoshiaki Kimura • Shingo Kataoka • Yuuichi Kanno • Kazuki Komai • Yoshiaka Kimura • Atsushi Masaki • Masanobu Matsunaga • Daisuke Matsuoka • Toru Minegishi • Naoko Mitome • Yasunori Mitsuda • Masato Mizuta • Hiroki Morishita • Shoh Murakami • Kyoko Miyamoto • Yutaka Minobe • Osamu Narita • Ryo Nagamatsu • Kenta Nagata • Shinobu Nagata • Akito Nakatsuka • Kenichi Nishimaki • Graeme Norgate • Eveline Novakovic • Genki Namura • Hideki Oka • Soyo Oka • Shinya Ohtouge • Satoshi Okubo • James Phillipsen • Mike Peacock • Darren Radtke • Suddi Raval • Motoi Sakuraba • Lawrence Schwedler • Yoshito Sekigawa • Ichiro Shimakura • Yoko Shimomura • Sanae Suzaki • Nobuyoshi Suzuki • Chika Sekigawa • Masayoshi Soken • Taiju Suzuki • Sara Sakurai • Aya Tanaka • Hirokazu Tanaka • Kazumi Totaka • Yuka Tsujiyoko • Seiichi Tokunaga • Tomoya Tomita • Masaru Tajima • Kumi Tanioka • Katsunori Takahashi • Satomi Terui • Brian Tyler • Toshiyuki Ueno • Shinji Ushiroda • Kazufumi Umeda • David Wise • Hajime Wakai • Hironobu Yahata • Natsuko Yokoyama • Kenichi Yoshimoto • Mahito Yokota • Chad York • Ryoji Yoshitomi | ||||

| Artists | Kevin Bayliss • Maude Church • Jeff Griffeath • Shigefumi Hino • Vince Joly • Yoichi Kotabe • Steve Mayles • Sho Murata • Shigehisa Nakaue • Leif Peng • Megan Rose Ruiz • Masanori Sato • Yukio Sawada • Mark Stevenson • Ko Takeuchi | ||||

| Writers | Doug Booth • †Véronique Chantel • Ian James Corlett • Phil Harnage • David S. J. Hodgson • Andrew Iverson • Leigh Loveday • Perry Martin • Michael Maurer • Claude Moyse • Peter Sauder • Ed Solomon • †Erika Strobel • Michael Teitelbaum • Tracey West • Ted Woolsey | ||||

| Historical figures | †Abraham Lincoln • †Albert Einstein • †Alexander Alexeyevich Gorsky • †Alexander Pushkin • †Andrey Chokhov • †Anne Hathaway • †Aristotle • †Benjamin Franklin • †Booker T. Washington • †Catherine Dickens • †Caesar Augustus • †Charles Dickens • †Charles-Gaspard de la Rive • †Christopher Columbus • †Cleopatra • †Constanze Mozart • †Deborah Read • †Diego Rivera • †Duke of Alençon • †Edmund Halley • †Feodor I of Russia • †Ferdinand Magellan • †Francis Drake • †Francis of Assisi • †Frederick Douglass • †Frida Kahlo • †Galileo Galilei • †George Washington Carver • †Gustave Eiffel • †Hadrian • †Henry Ford • †Ho Ti • †Isaac Newton • †Ivan the Terrible • †Joan of Arc • †Johann Gutenberg • †José Hernández • †Joseph Haydn • †Juan Sebastian Del Cano • †Julius Caesar • †Kublai Khan • †Leonardo da Vinci • †Lillian Hitchcock Coit • †Louis Pasteur • †Ludwig van Beethoven • †Mahatma Gandhi • †Mao Zedong • †Marco Polo • †Mary Todd Lincoln • †Michael Faraday • †Michelangelo Buonarroti • †Minamoto no Yoritomo • †Muhammad Ali • †Napoleon • †Nero • †Pierre Paul Emile Roux • †Plato • †Pope • †Queen Elizabeth I • †Raphael Sanzio • †Richard Burbage • Richard Leakey • †Royal Society • †Rufino Tamayo • †Sarah Barnard • †Thomas Edison • †Thomas Jefferson • †Ts'ai Lun • †William Shakespeare • †Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | ||||

| Other | Al Pacino • Andy Heyward • †Annette Funicello • Backstreet Boys • †Barbara Walters • †The Beach Boys • †The Beatles • Bill Gates • Bill Trinen • Brad Pitt • Britney Spears • †Bruce Lee • †Buddy Knox • †Charlie Foxx • Chris Meledandri • Christopher Griffin • Daisuke Matsuno • David Grenewetzki • Dayvv Brooks • Doug Bowser • Eddie Murphy • Erik Estrada • †Ernie K-Doe • †Frank Sinatra • †Gene Vincent • Hideyuki Nakayama • †Hiroshi Yamauchi • Howard Phillips • Hulk Hogan • The Human Beinz • †Inez Foxx • Jackie Chan • †James Dean • Jerry Lee Lewis • †Jim Nabors • †Joe DiMaggio • †Joe Jones • John Grusd • Keanu Reeves • Kevin • Kyōko Koizumi • Madonna • †Marilyn Monroe • †Mario Segale •Mel Gibson • †Michael Jackson • Michael Kelbaugh • Michelle Powers • Miyuki Nakajima • Noritake Kinashi • †Queen of England • Reggie Fils-Aimé • †Roger Ebert • †Satoru Iwata • Scott Baio • Shaq • Shuntaro Furukawa • †Sonny Bono • Sophia Loren • Steven Griffin • Sunplaza Nakano • Takaaki Ishibashi • Takeshi Kitano • Tatsumi Kimishima • Tom Cruise • Tommy James and the Shondells • Valerie Bertinelli • †The Ventures | ||||

| Mario's Time Machine | ||

|---|---|---|

| Super Mario characters | Bowser • Bowser's motherb • Donkey Kong Jr.c • Iggy Koopa • Larry Koopa • Lemmy Koopa • Ludwig von Koopa • Luigia • Mario • Roy Koopad • Yoshid | |

| Historical persons used as characters | Abraham Lincolna • Albert Einsteinc • Andrew Iversona • Anne Hathaway • Aristotle • Benjamin Franklin • Booker T. Washingtona • Catherine Dickensa • Charles Dickensa • Charles-Gaspard de la Rivea • Cleopatra • Constanze Mozarta • David Grenewetzkia • Deborah Reada • Don Lloyda • Duke of Alençon • Edmund Halley • Ferdinand Magellan • Francis Drake • Frederick Douglassa • Galileo Galileia • George Washington Carvera • Henry Forda • Ho Tia • Isaac Newton • Jeff Griffeatha • Joan of Arc • Johann Gutenberg • Joseph Haydna • Juan Sebastian Del Cano • Julius Caesar • Kublai Khan • Leonardo da Vinci • Louis Pasteura • Ludwig van Beethoven • Mahatma Gandhi • Marco Polo • Mary Todd Lincolna • Michael Faradaya • Michelangelo Buonarroti • Minamoto no Yoritomoc • Pierre Paul Emile Rouxa • Plato • Queen Elizabeth I • Raphael Sanzio • Richard Burbage • Royal Society • Sarah Barnarda • Thomas Edison • Thomas Jefferson • Ts'ai Luna • William Shakespeare • Wolfgang Amadeus Mozarta | |

| Enemies | Birdc • Bodyslam Koopac • Bullet Billa • Koopa • Mine • Pterodactyla • Sharka • Space Troopac • UFOc • Walking Turnipc | |

| Locations | Academy • Alexandria • Athens • Berlin Wallc • Bowser's castle • Bowser's Museum • Calcutta • Cambridge University • Cambuluc • Cretaceous Period • Egyptc • Florence • Germanyc • Gettysburgc • Gobi Desert • Independence Hall • Japanc • Kitty Hawkc • London • Luoyanga • Mainz • Menlo Park • Moonc • Novatoa • Orleans • Paduaa • Paradise • Parisa • Philadelphia • Stratford-upon-Avon • Swan Inn • Trinidad • Tuskegeea • Vienna • Washington, D.C.a • White Housea | |

| Items and objects | Almanaca • Apple • Art Filea • Astrolabe • Backscratcher • Balla • Bambooa • Beret • Booka • Book of Marco Polo • Bosun's Pipe • Bowa • Bowser Statue • Bread • Bucket of Plaster • Bucklea • Bug Fixa • Bug Reporta • Bunnya • Calculus Book • Cat • Chisel • Chocolatea • Clotha • Compassa • Conversations on Chemistrya • Crank Handlea • Crown • Cup of Tea • Declaration of Independence • Dictionarya • Dinosaur Eggc • Drawing of Air Screw • Drawing of Ideal Man • Drumstick • F=MA • Fan • Feather • Filament • Firecrackera • Fireworks • Flag (India) • Flag (United States of America)c • Flaska • Floppy Diska • Flutea • Football • Globe • Grape • Handkerchief • Hand Mirror • Horse's Bit • Hourglass Blockc • Ice Creama • Incense • Inkwella • Information boxc • Key (Mainz) • Key (Philadelphia)a • Knife • Ladder • Laurel Wreath • Law Book • Lemonadea • Lens • Light Bulbc • Magneta • Measuring Stick • Metal Type • Metronome • Milka • Mona's Mirror • Mona Lisa • Moneya • Monocle • Mushroom • Music • Newspaper • Notebook • Onion • Paint • Paintbrush • Paintinga • Pamphlet • Paper Money • Pearl Necklace • Pennya • Physics Equationc • Poetry Booka • Postcard • Principia • Print Block • Propellerc • Quill Pen (1602)c • Quill Pen (Orleans) • Rat Trap • Republic • Ricea • Scarfa • Scissors • Scripta • Scrolla • Shield • Skull • Sledgehammerc • Spectacles (Philadelphia) • Spectacles (Washington, D.C.)a • Sphinxc • Staff • Stampa • Starmanc • Steering Wheelc • Stovepipe Hatc • Swordc • Tea Bag • Telegram • Telescope (Padua)a • Telescope (Trinidad) • Thronec • Ticketa • Timulator • Tirea • Torchc • Toya • Turkeya • Turtle Cannonc • Watcha • Warp Pipec • Whirlpool • Wooden Snake | |

| Other | Staff | |